“My lord has not seen Iceland rise from the sea…” – Flatey in Breidafjordur, September 2013 (picture by Annette Rubery)

I wrote this longer-than-usual article in 2009 as a guest post on a blog about 18th century history, and it’s also appeared here as well. It’s meant as an introduction to a favourite novel by one of my literary heroes, the Icelandic Nobel laureate Halldór Laxness, and it’s not supposed to be definitive: it’s aimed at an English-speaking non-specialist readership, with no particular grounding in Icelandic literature or culture. I’ve had no further opportunity to write about Laxness or Icelandic literature, but I’d be very keen to do so! (Contains spoilers)

If you love the 18th century, chances are you have a favourite historical novelist. It’s a boom area in literature – and an opportunity for readers to slip, for a few hours, into a world of classical terraces, elegant ballrooms, colonnaded mansions and rolling parkland. But in the right hands, readers have shown themselves more than willing to move beyond the world of Jane Austen and into ever more exotic terrain. Rose Tremain’s 1999 Whitbread award-winner Music and Silence, for example, found a wide readership for a story set in the Royal court of 1630s Denmark.

So here’s a historical novel also set, in part, at the Danish royal court, covering (roughly) the period 1700-1730: the age of the Great Northern War. Epic in scope, it sweeps across nations and seas, a story of oppression, suffering and intrigue; of boisterous humour, deep poetry and star-crossed romance. It’s by a great novelist; in fact, a Nobel laureate. And yet it’s barely known in the English-speaking world. It’s called ĺslandsklukkan – Iceland’s Bell – and it’s by the Icelandic writer Halldór Laxness (1902-1998).

To be fair, until recently you’d have had to read it in Icelandic, or maybe German. Incredibly, Iceland’s Bell was only translated into English in 2003 (it was first published in 1945). Philip Roughton’s translation (which I’ve used throughout; with Icelandic letters such as đ [pronounced ‘th’] used about as consistently as Wordpress allows me) has only now given this extraordinary novel to English-speakers. But the 18th century-loving community still seems to have been rather slow to seize on it.

Maybe that’s because Laxness is best-known as a literary modernist; the author of powerful social-realist novels like Independent People (1934) and visionary psychedelia (Under The Glacier – 1968). You certainly wouldn’t guess from the cover of the Vintage edition that this was a historical novel. Maybe it’s because of the notorious English-speaker’s allergy to literature in translation (though if you can handle Tolkien’s imaginary names and places, you should be able to cope with Laxness’ genuine Icelandic ones). And maybe it’s because when you open Iceland’s Bell, you enter an authentic, brilliantly realised 18th century world that’s startlingly different from anything in Austen or Georgette Heyer.

How different? Well, here’s the oldest surviving building in the Icelandic capital, Reykjavík. It dates from 1762 – in other words, a good half-century later than the period chronicled in Iceland’s Bell:

At the start of the 18th century, Reykjavík simply didn’t exist as anything more than a tiny fishing settlement, and it doesn’t feature in Iceland’s Bell (for Laxness’ take on Reykjavík, try his enchanting coming-of-age novel The Fish Can Sing). But the fact that this was one of the biggest and most impressive residences in Iceland gives you some idea what to expect in the novel. True, it’s a story of noblemen, elegant ladies, country squires and great estates – but don’t picture Palladian mansions and jardins à l’anglaises. A couple of the locations featured in the novel survive today. Bessastađir, just outside modern Reykjavík, was the seat of the Danish regent, and it’s still the residence of the President of Iceland.

Bessastaðir today (Wikimedia Commons)

This is where Jón Hreggviđsson is imprisoned near the start of the novel, and although it was extensively rebuilt from the 1760s onwards, it’s still on the same site. Here’s how it looked at the start of the 19th century. Remember, in the period of Iceland’s Bell this was by some way the biggest and most impressive building in Iceland – and it wasn’t even as grand as the structures in this picture:

Bessastaðir in 1834

Only slightly less imposing were the houses of the Danish Monopoly Merchants – the officials licensed by the Danish crown to control and manage all trade with its colony of Iceland. From 1602 to 1786 trade with Iceland was rigorously controlled by Denmark, and in the period of Iceland’s Bell all trade was forbidden except through licensed Merchants in designated Monopoly Ports. The result, unsurprisingly, was poverty and famine. Most Icelanders were subsistence farmers or fishermen, living in turf-roofed cottages. (In the novel, Jón Hreggviđson is initially convicted as a “cord-thief”, and throughout Iceland’s Bell, a shortage of fishing-cord is reported as Iceland’s most urgent problem. Icelanders couldn’t even feed themselves without it). In such circumstances, the monopoly merchant’s houses were symbols of unimaginable power and wealth.

And when you look at the surviving examples – such as the Husiđ in the monopoly port of Eyrarbakki (1765), today a museum – it’s impossible not to do a double-take. This is the very house where Squire Magnús of Braeđratunga passes out in the pigsty after selling his wife for a keg of brennivín, in Part 2 of Iceland’s Bell (Laxness stayed in Eyrarbakki to complete the novel). It’s about as grand as Georgian architecture got in Iceland. And it’s not exactly Blenheim Palace:

Husiđ at Eyrarbakki

This is the world in which Laxness chose to set his great historical novel. Like many of his literary choices, it proved controversial amongst his fellow Icelanders. Laxness was at the height of his career; ten years later, in 1955, he’d be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. He worked on the book over the period 1942-45. On 17th June 1944, after seven centuries of foreign rule, Iceland finally achieved independence from Denmark – though with the superpowers already positioning themselves for the Cold War to come, the young Republic’s future looked far from secure. National pride, and nationalist passions, were burning high. Now, at this historic moment, Iceland’s leading writer published a novel set in the most humiliating period of Iceland’s history.

Laxness makes his intentions clear from his very first page:

There was a time, it says in books, that the Icelandic people had only one national treasure: a bell. The bell hung fastened to the ridgepole at the gable-end of the courthouse at Thingvellir by Oxará. It was rung for court hearings and before executions, and was so ancient that no-one knew its true age any longer. The bell had been cracked for many years before this story begins, and the oldest folk thought they could remember it as having a clearer chime. All the same, the old folk still cherished it.

The church at Thingvellir in 2009 – picture by Annette Rubery

Anyone who’s ever been on a “Golden Circle ” tour in Iceland will have visited Thingvellir – the breathtaking natural gorge where, for nearly a thousand years, the Icelandic Parliament, the Althingi met annually in the open air. Today it’s a World Heritage Site; a wooden church (dating from the 19th century) has replaced the 17th century courthouse. The old bell, sent as a gift to Iceland by King Olaf of Norway in 1015, and known to Icelanders under colonial rule as “the nation’s sole possession”, really existed. And what happens next – like many of the events in Iceland’s Bell – really happened, too:

One year when the king decreed that the people of Iceland were to relinquish all of their brass and copper so that Copenhagen could be rebuilt following the war, men were sent to fetch the ancient bell at Thingvellir by Oxará.

The king’s hangman comes from Bessasađir with a work party of convicts, and the bell is cut down.

The pale emissary took a sledgehammer from a saddlebag, placed the ancient bell of Iceland on the doorstep before the courthouse, and gave the bell a blow […] the bell broke in two along its crack.

The nation’s last treasure has been hacked down and shattered. Laxness’ message could hardly be more clear. He hasn’t just set his novel in the darkest period in Icelandic history – he’s beginning his story at its absolute lowest point. But there’s worse to come. There’s a famine, and an epidemic. By the end of Iceland’s Bell, the island itself has been put up for sale by the king of Denmark – and even he can’t find a buyer.

Meanwhile – and almost as an aside – Laxness has set his story in motion. As the cord-thief Jón Hreggviđson unwillingly cuts down the bell, he cracks a scurrilous joke about the king. That’s a criminal offence. The legal action that ensues becomes the driving force of the whole novel, expanding, twisting back on itself, and eventually, over three decades drawing the whole of Icelandic society into its coils – right up to the king of Denmark himself. It’s a classic Icelandic narrative gambit. Throughout the 1940s, Laxness was engaged in editing new editions of the medieval Icelandic sagas. The single, rash, action leading to a legal dispute that embroils the whole nation (and punctuated by set-piece courtroom battles at Thingvellir), is an archetypal saga narrative. Laxness conceived Iceland’s Bell as a modern saga, and the famous line from Njál’s Saga (known to every Icelander) is a sort of unspoken ground-bass to Iceland’s Bell: “With laws shall our land be built up, but with lawlessness laid waste”.

Laxness borrows a literary style from the sagas, too. We never read his characters’ thoughts or inner emotional conflicts. Like the anonymous saga poets, Laxness simply describes their words and actions – and lets us infer the emotions for ourselves. Instead of manipulating the reader’s feelings, Laxness prompts them. The effect is clear, objective and yet, at the book’s great climaxes, overwhelmingly moving.

And make no mistake, this is a story of epic range and emotion. Jón Hreggviđson’s decades-long struggle for justice is its backbone, and there’s no doubt that Hreggviđson – an illiterate, impertinent peasant-farmer, with seemingly endless reserves of stoicism and a head full of garbled medieval ballads – is the novel’s central figure. Hreggviđson (and the lawsuits he pursued from 1683 to 1715) really existed, but Laxness makes this near-forgotten 17th-century criminal a figure of universal significance.

Egill Skallagrímsson – from a 17th Century manuscript.

He’s the eternal underdog; resourceful, facetious and seemingly indestructible. Icelandic readers will have found traces of favourite saga-characters in his make-up – the buffoonish Björn from Njál’s Saga, the bullish Grettír the Strong, and of course the great trickster-poet Egill Skallagrímsson. English readers might be reminded of Baldrick. But Hreggviđson is very much his own man. Whether conscripted into the Danish army or wrestling with trolls on an Icelandic heath; flogged, abused, and pushed around by the mighty, he always comes back with the proud assertion that he’s descended from the saga-hero Gunnar of Hliđarendi – and throws in an apposite verse of his favourite Elder Ballad of Pontus.

Against his story, and intertwined with it, another very different narrative unfolds. And for many readers, the romance of the Lady Snaefriđur, “Iceland’s Sun”, and the King’s Antiquary, Lord Arnas Arnaeus makes Iceland’s Bell one of the most touching love stories in modern literature. Snaefriđur (literally “Fair as Snow”) is one of Laxness’ most beloved creations: daughter of Iceland’s senior magistrate, sister-in-law of the Bishop of Skálholt, she’s universally admired as Iceland’s loveliest and most nobly-born heiress. We meet her first as a figure from a fairy-tale:

She wore no hat, and her head shone with dishevelled hair. Her slender body was childishly supple, her eyes unworldly as the blue of heaven. Her comprehension was still limited only to the beauty of things, rather than to their usefulness, and thus the smile she displayed as she stepped into this house had nothing to do with human life.

“Snaefridur, Iceland’s Sun” – costume design from the 1950 National Theatre of Iceland stage version.

But Snaefriđur will soon learn about human life, and in full measure. Like Guðrún Ósvífursdóttir, the commanding heroine of Laxdaela Saga, she’s proud, determined and idealistic. She’s also in love – and is prepared to break the law, and bring about her own social and financial ruin rather than betray her emotions. One night at Thingvellir, she springs Jón Hreggviđson from the condemned cell and sends him with a ring and a message to her beloved in Denmark. Determined that if she can’t marry the “best of men”, she’d rather have the worst, she marries the brutish drunkard Magnús of Braeđratunga. Meanwhile she sacrifices her wealth, dignity and youth to pursue a long series of lawsuits against her true love, Arnas Arnaeus – who has ignored Hreggviđson’s message (but taken up his case), returned the ring, and quit Iceland in pursuit of a higher calling.

Guðrún Ósvífursdóttir’s grave, from Helgafell – photo by Annette Rubery

Fire in Copenhagen, the final volume of Iceland’s Bell is dominated by his story, just as the second, The Fair Maiden is dominated by Snaefriđur, and the first, Iceland’s Bell focuses on Jón Hreggviđson. Court Assessor Arnas Arnaeus, the Royal Antiquary, is the highest ranking Icelander at the Danish court, and at first sight he’s little more than another Restoration dandy:

The aesthete in him spoke out from every seam, each pleat, every proportion in the cut of his clothing; his boots were of fine English leather. His wig, which he wore under his brimmed hat even amongst boors and beggars, was exquisitely fashioned, and was as smartly coiffured as if he were going to meet the king.

But he enters Hreggviđson’s turf hovel in search of something more precious to him than his own status – fragments of old Icelandic parchments. His passion is the ancient literature of Iceland; to him, the proof that his stricken country once created great art. In his elegant Copenhagen townhouse, he collects a library of Icelandic sagas, ballads and poetry. Meanwhile he pays court (Fire in Copenhagen opens with a gorgeous set-piece description of a royal masque in the Danish capital), marries into money, and struggles to improve the lot of the Icelanders – making powerful enemies along the way. It’s all of it necessary to protect his priceless manuscripts, and sacrificing the love of his life is just part of the price that he decides to pay. The tragedy of their love is that Snaefriđur understands this too:

“Snaefriđur” he said as she turned to leave. He was suddenly standing very close to her. “What else could I have done but give Jón Hreggviđson the ring?”

“Nothing, Assessor”, she said.

“I wasn’t free,” he said. “I was bound by my work. Iceland owned me, the old books that I kept in Copenhagen – their demon was my demon, their Iceland was the only Iceland in existence. If I had come out in the spring on the Eyrarbakki boat, as I promised, I would have sold out Iceland. Every last one of my books would have fallen into the hands of my creditors. We would have ended up on some dilapidated estate, two highborn beggars. I would have abandoned myself to drink and would have sold you for brennivín, perhaps even cut off your head –“

She turned completely around and stared at him, then quickly took him by the hand, leaned her face in one swift movement up against his chest, and whispered:

“Arní.”

She said nothing more, and he stroked her fair and magnificent hair once, then let her leave as she had intended.

The Great Fire of Copenhagen – contemporary print

Laxness based Arnas on the great Icelandic antiquarian Árni Magnússon (1663-1730). Magnússon, like Arnas Arnaeus, built a collection of Icelandic manuscripts in Copenhagen; and like him, led a troubled personal life. And his collection, too, was badly damaged in the Great Fire of Copenhagen in 1728, which forms the dramatic climax of Iceland’s Bell. But unlike Arnas’, it wasn’t completely destroyed. Three decades after Iceland gained independence, and Iceland’s Bell was published, the Danish government started to repatriate the Magnússon collection. Today, the manuscripts are protected by the Árni Magnússon Institute in Reykjavík, and the room that displays them in Reykjavík’s Culture House is a place of pilgrimage for lovers of European literature.

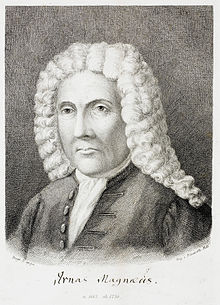

Arni Magnusson

Halldór Laxness doesn’t have quite such a happy end in store for his characters. But he wouldn’t be the writer he is if he didn’t somehow find hope in even the bleakest of circumstances. At one point in the novel, Arnas comments that his countrymen’s “one and only task is to keep their stories in memory until a better day”. In the closing pages of Iceland’s Bell, his life’s work is in ashes, Iceland is more abject than ever, and he has sacrificed love and career in vain. But one thing – one person – has survived it all; the indomitable Jón Hreggviđsson and his head full of poetry. Together, they ride to the harbour where Hreggviđsson, pardoned at last, is to take ship back to Iceland. And as always, the illiterate cord-thief has a verse for the occasion:

“Now I shall teach you an introductory verse from the Elder Ballad of Pontus, that you have never heard before,” he said.

Then he recited this verse:

“Folk will marvel at the story,

There on Iceland’s shore

When Hreggviđsson’s old grey and hoary

Head comes home once more.”

After both had memorized the verse, they all sat in silence. The road was wet, causing the carriage to sway from side to side.

The Assessor remained lost in thought for some time, then finally looked at the farmer from Rein, smiled and said:

“Jón Marteinsson saved the Skálda. You were all that fell to my lot”.

Jón Hreggviđsson said: “Does my lord have any messages he would like me to deliver?”…

“You can tell them from me that Iceland has not been sold – not this time. They’ll understand later. Then you can hand them your pardon”.

“But shouldn’t I convey any greetings to anyone?” said Jón Hreggviđsson.

“Your old ruffled head – that shall be my greeting” said the Professor Antiquitatum Danicarum.

Arnas Arnaeus gives his life to the written word. Jón Hreggviđsson can’t even write, but his nation’s literary culture bubbles, unquenchably, beneath his “old ruffled head”. It takes a writer of Laxness’ vision to perceive that a nation’s literature can survive without books – but not without its humanity. When Laxness was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1955, the Swedish Academy’s citation was:

For his vivid epic power, which has renewed the great narrative art of Iceland.

None of his novels embodies that spirit more stirringly than Iceland’s Bell. And nothing captures the spirit of the novel better than Laxness’ response to his career’s crowning moment. As the telegrams of congratulations poured in from around the world, Laxness realised that he couldn’t respond to them all. So he decided to respond only to one – a message of “lycka til” [congratulations] from the Sundsvall Society of Pipe Layers, in northern Sweden. In other words, sewage-workers. Praised by the whole world, Laxness was moved above all by the idea that “men who bent double over pipes, deep in the ground, should climb out of their drains in the midst of the winter in Sundsvall, in order to shout ‘hurrah for literature’”.

August 2009