So here it is, Merry Christmas, and we have it on unimpeachable authority that everybody is having fun. Forgive me: I lived in Wolverhampton for eight years (well, it was good enough for Percy Young) and Noddy Holder is like a god there.

I’m not the world’s greatest fan of seasonal pop music. But I am, however, a fan of Victor Hely-Hutchinson’s A Carol Symphony – a work with a deep connection to the English Midlands, and not just through its association with successive dramatisations of The Box of Delights. Here’s a blogpost I wrote in 2009 about the music and its (largely forgotten) composer. When it was first published I was delighted to receive a charming and kindly email from the composer’s then-78 year old son Christopher, who was living in Ludlow. Hopefully he still is. Happy Christmas!

Victor Hely-Hutchinson (1901-1947)

When I was 11, my younger sister and I were both captivated by the BBC’s TV adaptation of John Masefield’s The Box of Delights. She liked the fantastic story, and the Christmassy atmosphere; I liked the steam trains. But one thing that we both loved, and which seemed to capture the whole wintry magic of the thing, was the signature tune – which we could tell, even then, was “proper” music, not just a typical children’s TV theme (this being the early 1980s, the lack of synthesizers was the giveaway). Here’s that title sequence in full (warning, unseasonably noisy Youtube advert may play first!).

I asked my father if he knew what it was – not realising that a pre-war radio dramatisation of The Box of Delights, with the same music, had become a seasonal classic for an earlier generation. Or that my father – at much the same age – had asked exactly the same question. He pulled out a Classics for Pleasure LP with a snowy landscape on the cover. The piece on it was called Carol Symphony, and the composer was Victor Hely-Hutchinson.

Sleeve art the way it used to be.

The record-sleeve told us that he’d been born on Boxing Day 1901, and had been Regional Director of Music for the BBC in Birmingham. It wasn’t very easy to find out much more back then, but it is now, and for the full story, there’s an excellent online biography by his son John. In short, Christian Victor Hely-Hutchinson was born in Cape Town, studied music with Charles Villiers Stanford and Donald Tovey, and at the age of 12 played a Mozart piano concerto with the LSO. In 1933 he landed the Birmingham job, and rapidly involved himself with every part of the city’s musical life – not least the 13-year old City of Birmingham Orchestra and its then music director Leslie Heward.

Hely-Hutchinson never held an official post with the CBO – but he was a tireless supporter of the Orchestra throughout the 1930s and 40s. The CBSO’s performance record-cards from that period are dotted with the initials VHH – indicating that he’d written the programme notes for a particular work. He gave pre-concert lectures (he took a doctorate in 1941, though he’d held the Chair of Music at Birmingham University since 1934). He appeared as piano soloist with the orchestra, notably in Mozart concertos, and in 1944 he performed his own rhapsody The Young Idea (intriguingly subtitled “cum grano salis”) with George Weldon conducting. It’s recently been recorded by Dutton.

And he did it all with consummate professionalism. The CBO’s manager Gerald Forty (of the piano-makers Dale, Forty) remembered that:

His quiet confidence was most reassuring. I see him in my mind’s eye, sitting at my desk. He knocks out a half-smoked pipe, his inseparable companion: fills it, lights it, takes a few puffs – finds it won’t draw – scrapes it out, refills it, wastes more matches – and so on da capo. While my ashtrays were being filled, his mind was concentrated on the matter at hand, and with a remarkable economy of words, he stated his views and recommended a solution.

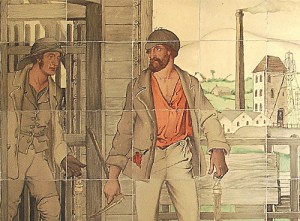

Leslie Heward

But it was during wartime that Hely-Hutchinson gave his greatest service to the CBO. In early 1940, while working as a volunteer Air Raid Precaution warden, he performed (from memory!) a complete cycle of Beethoven Piano Sonatas at the Birmingham and Midland Institute – in aid of Orchestra funds. Meanwhile, he corresponded regularly with Leslie Heward, then recovering in Romsley Sanatorium from the TB which was to kill him just three years later. When Heward died in May 1943, Hely-Hutchinson rallied to the support of the CBO. As Forty recalled:

Birmingham Town Hall in wartime. Hely-Hutchinson took part in ARP fire drills on the roof.

The problem of finding another conductor at short notice and of maintaining a full complement of players with War staring us in the face, was one of extreme perplexity; but Victor solved it by the apparently simple expedient of doing the entire job himself – including the compiling of programmes, rehearsing the orchestra (which he did anonymously and gratuitously for many years), conducting the concerts and dealing efficiently and decisively with the innumerable emergencies…

Hely Hutchinson was initially unconvinced by Heward’s successor, George Weldon, but with typical fair-mindedness was happy to revise his opinion after Weldon had settled into the post a year or so later:

“I want to tell you how right I think you were about George Weldon – and by the same token, I was wrong – eighteen months ago” he wrote to a colleague in June 1944. “As a pure musician, I cannot think him the equal of Leslie, but then, practically nobody is, and some of George’s performances – notably of Mozart – made me feel that he has the root of the matter in him”.

The following year, Hely-Hutchinson was offered the post of Director of Music for the BBC in London, and swapped his home near Droitwich for one in St John’s Wood. But he remained a familiar face in Birmingham music, and there was genuine shock in the city in March 1947 when the news arrived that he had died of pneumonia, aged just 45. The CBO paid its own tribute three weeks later, when Weldon conducted the first performance of Hely-Hutchinson’s recently-completed Symphony for Small Orchestra. (The concert was broadcast, and an incomplete recording survives in the CBSO archive).

Somehow, in this short but full musical life, Hely-Hutchinson found time to compose around 150 original works. The best known (by a country mile) is the Carol Symphony, from 1927, but there’s also an irresistible setting of Old Mother Hubbard “in the style of Handel”, which amusingly skewers the absurdities of baroque vocal style; and two shorter works, the Overture to a Pantomime and The Young Idea. Both have recently been recorded. They all show superb craftsmanship, a masterly ear for orchestral colour and a warm, thoroughly engaging sense of musical humour. They’d all merit an outing in the concert hall.

But the Carol Symphony has never quite left the repertoire (the most recent Birmingham performance was in December 2000). Far more than a mere seasonal medley, it’s actually a lovely and very English folk-song sinfonietta in four movements, in the spirit of Moeran, Vaughan Williams and John Ireland.

It’s packed with good things: the bustling mock-baroque figuration of the first movement (a sort of chorale-prelude on O Come All Ye Faithful), the jazzy, Walton-esque verve of the scherzo (God Rest Ye Merry); splashes of Handel, Elgar, and polytonal Stravinsky; the way Here We Come A-Wassailing trips in on the woodwind as the fugal finale bounds towards its grand, horn-trilling finish. And above all, that slow movement, in which Hely-Hutchinson sets the Coventry Carol to bleak, frozen harmonies that anticipate Vaughan Williams’ Sixth – and then, with dancing harp, muted strings and finally full orchestra, lightens our darkness with the gentlest and most enchanting setting ever made of The First Nowell.

A Box of Delights, indeed. Whatever else we remember him for, in the Carol Symphony Victor Hely-Hutchinson gave us something very special, and enduringly beautiful. Hely-Hutchinson’s CBO colleague and friend Gerald Forty, once more:

The Carol Symphony has become a standard Christmas piece for the City Orchestra: may it long continue to figure in those programmes as a reminder of the well-loved man to whom the City of Birmingham Orchestra and the Birmingham musical public owes so much.

Any copyrighted material is included as “fair use” for critical analysis only, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s).