Posted by richardbratby | Filed under Uncategorized

30 Saturday Apr 2016

Posted by richardbratby | Filed under Uncategorized

29 Friday Apr 2016

Posted in Uncategorized

Tags

Birmingham Post, English Touring Opera, Gavin Plumley, Gramophone, Johann Strauss, Mozart, Opera North, The Arts Desk, The Spectator, Welsh National Opera

Twenty minutes ago in Lichfield we had a hailstorm. Now it looks like this:

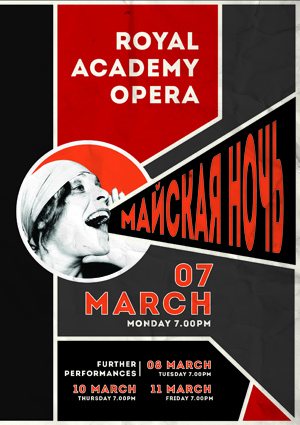

I’ve given up trying to wrap my head around the seasons because this month it’s been pretty much non-stop scribble scribble scribble, as George III supposedly said to Dr Johnson. I’ve had reviews in The Spectator for Birmingham Conservatoire’s Anglo-French triple-bill and the RAM’s May Night, reviewed a new opera and a Shakespeare celebration for The Birmingham Post and taken the road to Buxton to cover English Touring Opera’s spring season (well, 2/3 of it) for The Arts Desk. Not that I need much excuse to visit Buxton Opera House: this has surely got to be Britain’s best drive to work. Bit of RVW on the stereo: magic.

And last night I heard the UK premiere of a masterpiece – also for The Arts Desk.

On top of that, I’ve been working with The Philharmonia, Performances Birmingham, the CBSO and Warwick Arts Centre on their 16-17 season brochures. It’s a privilege to see what’s coming up next season but a couple of things are so exciting that it’s been quite hard to bite my tongue. And programme notes for two great festivals: four heavyweight programmes for Salzburg – any chance to write about Mozart is always a pleasure – and a whole raft of really wonderful English music, including some real favourites of mine, for the Three Choirs (it’s in Gloucester this year, btw).

Those came courtesy of two great colleagues, Gavin Plumley (he’s got a Wigmore Hall debut coming up and knowing the care and expertise he brings to everything he does, it should be superb) and Clare Stevens, who’s currently blogging the story of her grandmother’s experiences in the Easter Rising of 1916: a really remarkable piece of family history. I’ve also written about a couple of fascinating programmes for the Wigmore Hall and the Barbican and an article on Verdi’s Falstaff for the CBSO’s in-house magazine Music Stand. And did you know that Arthur Bliss wrote a Fanfare for the National Fund for Crippling Diseases? Don’t ask…

And that’s not to mention my most exciting project so far for Gramophone: a reassessment of Carlos Kleiber’s classic 1976 recording of Die Fledermaus, co-written (to my astonishment and awe) with one of the greatest living experts on operetta, Andrew Lamb. A huge privilege and actually enormous fun; I think it’s being published in the July edition, though meanwhile Gramophone has been keeping me busy with everything from Johann Strauss and Balfe to Cecil Armstrong Gibbs. Full list here. They know me too well already…

Anyway, tonight it’s Mark Simpson’s new opera Pleasure at Opera North (for The Spectator); the next few weeks of opera-going will take me to Guildford, Cardiff, Wolverhampton and Glasgow, so if I’m quiet again for a bit, my apologies.

29 Friday Apr 2016

Posted in Uncategorized

Tags

The Birmingham Post isn’t always able to post online everything that I’ve written for its print edition, so – after a suitable time lag (you should really go out and buy the paper!) – I’ll be posting my recent reviews here. As per the print edition, they’re all fairly concise – just 250 words. This is of a performance at Kidderminster Town Hall on Saturday 19 March.

Handel’s The King Shall Rejoice, Haydn’s Nelson Mass and Mozart’s anything-but-solemn Solemn Vespers – the Kidderminster Choral Society clearly likes to keep itself busy. This was a concert of pretty much wall-to-wall choral singing, and none the worse for it: three top-flight masterpieces delivered with energy and zing under the Society’s artistic director Geoffrey Weaver.

And that was despite the stage arrangements at Kidderminster’s Victorian Town Hall – which split the choir in two and stacked them steeply on either side of the organ. The KCS is clearly well-used to this: they produced a big, bright mass of sound, with a brilliant soprano section and a more than usually lively team of altos. In the Haydn, they sounded like they were enjoying every note. Weaver kept it bowling along and the choir responded with lively, natural phasing and crisp, clearly enunciated interjections in the Gloria.

Perhaps he might have paced the Benedictus to make more a climax out of the arrival of Haydn’s warlike trumpets – but there was no doubt that the spirit of the thing was there in spades. It helped that they had such a winningly youthful line-up of soloists: contralto Elisabeth Paul, tenor Christopher Fitzgerald-Lombard and bass Andrew Randall. But the real heroine of the evening was the soprano Gemma King, standing in at one day’s notice, and singing with a pure, vibrato-light tone and such smiling freshness that you’d never have known it.

A couple of caveats: there’d be room in the nicely-produced programme book for the text and translations – these should be provided as a matter of course. And as Richard Strauss once said: don’t look at the trombones, it only encourages them. Throughout the first half, one of the Elgar Sinfonia’s trombonists (unnamed in the programme) honked it out so noisily that any chance of distinguishing the chorus’s words was obliterated, at least from where I was sitting.

23 Wednesday Mar 2016

Posted in Uncategorized

The Birmingham Post isn’t always able to post online everything that I’ve written for its print edition, so – after a suitable time lag (you should really go out and buy the paper!) – I’ll be posting my recent reviews here. As per the print edition, they’re all fairly concise – just 250 words. This is of a performance at Codsall Community Arts Festival on Tuesday 15 March.

You’ve got to hand it to the Codsall Community Arts Festival. Many festivals simply pick their concert programmes from a set menu provided by the ensemble. But at Codsall, having made the Great War a theme, they contacted Gloucester Library, sought out the manuscript of Gurney’s incomplete String Quartett [sic] of 1918-19, and persuaded the Klee Quartet to play it alongside Purcell’s Fantasia No.12 and – seriously – György Kurtág’s Six Moments Musicaux.

That would be a risky programme even at Birmingham Town Hall. I’m pleased to report that St Nicholas’s Church was well filled and that the audience listened with every sign of intense concentration, barring the lady next to me who unwrapped and munched a Mars Bar in the second movement of the Gurney. Did it work? The first half certainly did.

The Tokyo-based Klee Quartet – currently studying at Birmingham Conservatoire – plays with subtlety, style and intense commitment. They began the Fantasia without vibrato, gradually starting to colour Purcell’s plaintive D minor phrases as the music unfolded. Then they launched straight into the Kurtág – with passion, precision and a range of colours that made every pizzicato slide or barely-audible sul ponticello shiver tell its own story. Above it all, leader Naoko Senda’s rich, ardent tone left no doubt that we were hearing emotion as well as fierce intelligence.

If only they’d managed to get quite so completely inside the Gurney: though much as it hurts to say it, maybe there isn’t really very much to get inside. It’s tender and lyrical: it’s also rambling and diffuse. The Klees were clearly game, but even they couldn’t quite convince you that there were worthwhile ideas to be found beyond the ravishing first theme of the Adagio. Still, Gurney needs to be heard, and thanks to the Codsall Festival he was. That’s something.

19 Saturday Mar 2016

Posted in Uncategorized

So, the morning after we saw Birmingham Conservatoire’s production of Vaughan Williams’s Riders to the Sea, we drove to Bath. It was a beautiful clear day and the roads were empty, so at Cirencester we decided to take a slight diversion – and make a long-intended pilgrimage to Ralph Vaughan Williams’s birthplace, the Cotswold village of Down Ampney.

I’d always lazily pictured it in some little Gloucestershire valley or on a hillside, like Painswick or the Slaughters. In fact, it lies some miles behind the Cotswold escarpment in wide open countryside, rolling so gently that it’s practically flat.

Other than that, it’s much as you’d expect – quiet, certainly not coach party-pretty, but extremely pleasant: birdsong was in the air on this March afternoon, and there’s clearly as much going on as you’d imagine in any medium-sized English village.

There’s no museum or monument to RVW. And unless you’ve done your homework, there’s no outward sign to tell you that the village’s Old Vicarage was the birthplace of Britain’s greatest symphonist post-Elgar. We didn’t hang around outside; it’s clearly still a family home and anyone who’s ever lived in an Oxford college knows what it’s like to look out of your living room window and see a tourist camera pointed straight back. It’s shielded from the road by thick yew hedges. We didn’t want to turn into stalkers, so we walked on.

Instead Down Ampney wears its connection to RVW modestly, but with quiet pride – exactly how you suspect he’d have wanted it. The focus for pilgrims is the village church of All Saints, located next to the manor house down a quiet lane about 10 minutes’ walk from the village centre.

It’s not all about RVW. There was an RAF base in the nearby fields during World War 2 and the churchyard has numerous war graves. There’s also a Victorian stained glass tribute to Vaughan Williams’ father, the Rev Arthur Vaughan Williams, who was vicar of Down Ampney at the time of Ralph’s birth. The church is unlocked during daylight, though a sign on the door warns you to shut it firmly after you “as birds find the interior fascinating”.

And there’s a small but very comprehensive exhibition about the composer at the back of the church, provided by the RVW society.

But the best finds were the little things that show that so many years later, RVW is still a presence in the life of this church and community – we spotted this embroidered hassock. And the music of the hymn Come Down O Love Divine was pinned to the organ – to the tune, of course, that Vaughan Williams wrote in 1904, and called (what else?) “Down Ampney”.

19 Saturday Mar 2016

Posted in Uncategorized

Tags

Birmingham Hippodrome, Reviews, The Birmingham Post, The Marriage of Figaro, Welsh National Opera

Elizabeth Watts & Mark Stone (Countess & Count Almaviva) – picture by Richard Hubert Smith

The Birmingham Post isn’t always able to post online everything that I’ve written for its print edition, so – after a suitable time lag (you should really go out and buy the paper!) – I’ll be posting my recent reviews here. As per the print edition, they’re all fairly concise – just 250 words. This is of a performance at Birmingham Hippodrome on Wednesday 23 March, a sort of addendum to my Spectator review of the opening night in Cardiff a fortnight earlier.

At the very end of The Marriage of Figaro, as the Almaviva household’s crazy day races towards its conclusion, the betrayed Countess declines her revenge and instead forgives her jealous, philandering husband. Done well, it’s one of the most poignant moments in all Mozart – in other words, in all of theatre.

In this new production from Welsh National Opera, it wasn’t just the great, compassionate glow that flooded from Lothar Koenigs’ orchestra that made the eyes well up. It wasn’t even Elizabeth Watts’s radiant singing as the Countess. It was the way Watts took the Count (Mark Stone) by the hand and for the first time in the whole evening, looked him in the eye. One little detail, a single moment of human contact – and yet one that summed up everything that made director Tobias Richter’s achievement so utterly glorious.

It fizzed. It sparkled. And with a near-ideal cast, everyone played joyously off each other. In David Stout’s witty, handsomely-sung Figaro and Anna Devin’s sunny, spirited Susanna, Richter had a central couple who were both entirely believable and enormous fun to be around. With her gawky movements and sweet but plangent tone, Naomi O’Connell’s Cherubino was the girl-crazy teenage boy to perfection.

As Basilio, Alan Oke rolled his r’s with deliciously pedantic relish, while Richard Wiegold’s Bartolo and Susan Bickley’s Marcellina managed the transition from pantomime baddies to doting parents with genuine charm. And under Richter’s direction, even the Count evoked sympathy, Stone’s features crumpling with the frustration and puzzlement of a man who’s essentially weak rather than bad.

Sue Blane’s colourful mock-Georgian costumes gave the whole thing the tiniest spice of artificiality – just enough to make it ping off the stage. And to hear the clarity and comic timing these singers brought to their lines (in Jeremy Sams’ translation), with an audience laughing in real time, was a vindication of WNO artistic director David Pountney’s decision to have it sung in English. Ralph Koltai’s semi-abstract sets won’t have been to all tastes, but they focused attention on what really mattered: the warmth of the human comedy unfolding beneath them, and some of the freshest singing and acting you could possibly hope for. In short, if you get a chance to see this production, take it. It’s basically perfect.

08 Tuesday Mar 2016

Posted in Uncategorized

Tags

Harry Bicket, Iestyn Davies, Reviews, The Birmingham Post, The English Consort, The Spectator, Welsh National Opera

Nicholas Lester in WNO’s The Barber of Seville. Robbie Rotten, I’m telling you.

The Birmingham Post isn’t always able to post online everything that I’ve written for its print edition, so – after a suitable time lag (you should really go out and buy the paper!) – I’ll be posting my recent reviews here. As per the print edition, they’re all fairly concise – just 250 words. This is of a performance at Birmingham Town Hall on Friday 26 February.

Other recent reviews include my takes on WNO’s Figaro Forever trilogy in The Birmingham Post and The Spectator.

Dr Johnson defined opera as “an exotic and irrational entertainment” – and for Exhibit A, he could have taken Handel’s Orlando. No opera can be judged fairly from a concert performance. But with the non-musical drama stripped out, Orlando’s high-voiced heroes, grandiose rhetoric and supernatural interventions veer dangerously towards Monty Python. By the umpteenth time that someone in this concert performance by Harry Bicket and The English Concert threatened to kill themself over love, honour or whatever, the Town Hall audience was openly laughing.

Why wouldn’t they? This was a terrifically entertaining evening, and the performances were uniformly superb. Bicket had assembled a dream cast. Countertenor Iestyn Davies blazed as the antihero Orlando, before delivering more reflective passages in tones so mellow that they almost seemed too lovely for a character who’s basically the ex-boyfriend from hell. In the trouser role of African prince (and dreamboat) Medoro the rich-voiced mezzo Sasha Cooke came across with a really masculine air of pride, while Kyle Ketelsen as Zoroastro looked every inch the magus in white tie and tails – and delivered majestic, ringing sound to match.

But at the centre of the drama are the oriental queen Angelica and the shepherdess Dorinda – and Erin Morley and Carolyn Sampson were ideal in every way. Morley’s light, brilliant soprano despatched Handel’s glittering coloratura with jewel-like clarity and poise, while Sampson’s vocal purity and grace made her the picture of pastoral innocence – until the moment in Act Three when, overcome by emotion, her voice deepened and darkened thrillingly and she brought the house down.

Bicket and his band responded exuberantly to Handel’s every detail, the continuo players swathing Angelica’s entrance in great flourishes of sound, and basses digging grittily in as Orlando descended into madness. The only way they could have served Handel better would have been with a fully-staged production.

04 Friday Mar 2016

Posted in Uncategorized

Tags

Balakirev, Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov, Royal Academy of Music, The Spectator, Wrexham Symphony Orchestra

I’ve never made any secret of my huge enthusiasm for the music of the Russian Nationalist school – the “Mighty Handful” and their successors – and I’m really looking forward to reviewing the Royal Academy of Music’s production of Rimsky-Korsakov’s A May Night on Monday. Along with its wintry, similarly Gogol-inspired sister-piece Christmas Eve, it’s my favourite of Rimsky’s operas – its gorgeous little overture was a highlight of my father’s Melodiya LP collection when I was growing up – but UK productions are very few and far between. The Russian nationalist-romantic composers have suffered disproportionately in the great narrowing of the standard repertoire that’s taken place in recent years, to the point where even an unarguable masterpiece like Borodin’s Second Symphony is now an exotic rarity in the concert hall. And of course the situation’s far worse for opera, making this student production doubly welcome. This’ll be the first time I’ve actually seen it staged, and I’m chuffed that my father’s able to come along too, after all these years of knowing it only from vintage Russian recordings.

To get in the mood, I’ve been looking through my personal Rimsky archives. His My Musical Life is one of my all-time favourite musical memoirs, and I’ve been waiting for years for someone to commission me to write about Rimsky, Borodin or Balakirev – to little avail. Here, though, is a programme note I wrote back in 2001 (so forgive the slightly classroom-y style; I was finding my feet) for Rimsky-Korsakov’s Third Symphony. Inevitably, this wasn’t for a professional orchestra but for my beloved Wrexham Symphony Orchestra (I was playing in the cello section), with Mark Lansom conducting. I’m not aware of a single UK professional performance of this fine work in the 15 years since.

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908)

Symphony No.3 in C major, Op.32

Moderato assai – Allegro

Scherzo: Vivo

Andante

Allegro con spirito

Musicians in late 19th Century Russia divided into two camps. The composers of the Moscow school, led by Anton Rubinstein, were trained along western lines and wrote symphonies, sonatas and concertos on the model of Mendelssohn and Schumann. But from the early 1860s a very different group of composers gathered around Mily Balakirev in St. Petersburg. Devoted to the memory of Russia’s first great composer, Mikhail Glinka, they were motivated by ideals of national pride and sought to create a music that was distinctly Russian in character, preferring to avoid western models. They were also amateurs. Of the so-called “Mighty Handful” – Balakirev and his four closest followers, Cui, Borodin, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov – none had received any significant formal training and only one, Rimsky-Korsakov, made a full time career out of music. They were fiercely defensive about their abilities and beliefs, and about their independence of Russia’s “westernised” musical establishment.

So when a member of the “Handful” set out to write a symphony, he was making a very public point about his technical skill and his ability to match western composers on their own terms. No composer was more aware of this than Rimsky-Korsakov. In the summer of 1871 he was offered an appointment as Professor of Practical Composition and Instrumentation at the St. Petersburg Conservatoire. Despite having two symphonies and numerous other major works to his credit, he wrote that “at the time I could not even harmonise a chorale; not only had I not written a single counterpoint in my life but I had hardly any notion of the structure of a fugue…my ideas of form were vague… even though I had orchestrated my own music so colourfully, I had no idea about string technique or the transpositions of horns, trumpets and trombones”.

Rimsky worked furiously to make up the deficiencies in his training, keeping just one step ahead of his pupils, and by the end of his 30-year Conservatoire career he was one of the most respected teachers in Russia. But in his early years he was intensely aware of his limitations. He’d written symphonies before, but the First had been a student exercise, dating from his time in the Russian navy, and the Second, “Antar” had effectively been a symphonic suite. Writing a new symphony, in the best classical manner, seemed an excellent way to develop the new skills he was so rapidly acquiring – and would give public proof of his professional competence.

He began composition in spring 1873. “Work was slow, however, and beset with difficulties. I strove to crowd in as much counterpoint as possible; but being unskilled in it and hard put to combine the themes and motives, I drained my immediate flow of imagination. The cause of this was, of course, my insufficient technique…” The symphony was completed on 18th February 1874, and, even with his own reservations, Rimsky-Korsakov must have been a little disappointed with the guarded reaction of his musical friends. Borodin called him “ a professor who has put on his spectacles and composed ‘Eine Sinfonie in C’ fitting such a title”. Mussorgsky’s reaction was less moderate: “The ‘Mighty Handful’ has hatched into a horde of soulless traitors!” Only in 1875, after the first Moscow performance, did the new symphony receive an enthusiastic review. The critic was Tchaikovsky, and Rimsky-Korsakov evidently had enough faith in his judgment to “compose the Symphony anew” in the summer of 1886. It is performed in this revised form today.

The Third Symphony is a far more “Russian” work than its early detractors allowed, and is anything but cold or academic. It bears a striking resemblance to Balakirev’s magnificent First Symphony (1898), with which it shares its key-signature and movement-plan, and it’s quite possible, since Balakirev spent an astonishing 32 years writing his work (and the “Handful” regularly shared their work-in-progress) that the two Symphonies influenced each other. Rimsky certainly heard Balakirev play many of his early symphonic sketches in the 1860s. In its own right, though, it is a hugely appealing and enjoyable romantic symphony. Although none of its main themes are actual folksongs, they have an unmistakably Russian cut, and the orchestration glows throughout with Rimsky’s colourful and very distinctive brass and wind writing.

The individual movements, too, are anything but formal academic exercises. The vigorous main theme of the first Allegro is a transformation of the flowing, chant-like “motto theme” which opens the symphony. The sweet second subject, introduced by a touchingly hesitant solo clarinet, strikes a note of real feeling, and goes on to provide the main material of the development section. This is anything but a conventional sonata-movement, however, and after a powerful recapitulation of the motto theme the movement proceeds, not to a grand C major coda but a quiet wind-down to a sombre C minor conclusion. The Scherzo is also highly original, not so much in form as in thematic material. It is in 5/4 time; as Mark Lansom has pointed out, possibly the first symphonic movement ever to be set in this time signature, predating comparable movements in Borodin’s Third and Tchaikovsky’s Sixth symphonies by well over a decade. Rimsky-Korsakov had sketched it in 1863; the sinuous Trio section had a rather more immediate personal association – he’d conceived it on an Italian lake steamer during his honeymoon in the summer of 1872.

Written in a warm E major, the Andante follows the formal pattern pioneered by Glinka in his Kamarinskaya, one of the musical touchstones of the “Mighty Handful”. Russian folk-melody doesn’t lend itself to development so Glinka simply repeated his themes in ever more varied orchestral colours, and this is exactly what Rimsky does with the very folksy principal subject of his slow movement. The tempo increases briefly in the centre of the movement and then relaxes again before accelerating into the Finale, which follows without a break. The processional melody for full orchestra that launches the movement soon acquires a more lively syncopated profile with a distinct whole-tone flavour, and this, together with a lyrical second theme in canon, provides the material for another spirited Rimskyan essay in sonata form. As the symphony approaches its close, Rimsky-Korsakov pays one more tribute to Glinka by quoting the descending whole-tone scale from his “Ruslan and Ludmilla” overture and ends with the triumphant C major peroration he denied us in the first movement, the “motto theme” with which the symphony opened pealing out in the brass amidst the general jubilation.

02 Wednesday Mar 2016

Posted in Uncategorized

Tags

Gramophone, Monocle, Programme Notes, Reviews, The Arts Desk, The Birmingham Post, The Spectator

Since I posted at the end of January, I’ve written programme notes on the following works. I’ve also published reviews in Gramophone, The Spectator, The Arts Desk and a few times in The Birmingham Post. And – for reasons that still remain unclear to me – appeared on Monocle Radio. This is why I’ve been a bit remiss with the blog. I’ll try to be better…

Albeniz: Suite Espagnole

Bach: D minor Chaconne

Bartók: Violin Concerto No.1

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.2

Beethoven: Piano Sonata in D minor (“Tempest”)

Beethoven: Piano Trio Op.70 No.2

Brett Dean: Wolf-Lieder

Bridge: Two Old English Songs

Britten: Frank Bridge Variations

Bruch: Eight Pieces Op.83

Debussy: Images

Delius: The Song of the High Hills

Falla: Fantasia Baetica

Glazunov: Grand Adagio from “Raymonda”

Haydn: Fantasia in C

Holst: Song of the Night

Honegger: Pacific 231

Lalo: Symphonie Espagnole

Mendelssohn: Violin Sonata in F (1838)

Oliver Knussen: Ophelia Dances

Rodgers and Hammerstein Gala

Rodrigo: Fantasia para un gentilhombre

Scarlatti: Five Sonatas

Schubert: Rosamunde incidental music

Schubert: Four Moments Musicaux

Schumann: Marchenerzahlungen

Sibelius: Symphony No.5

Sibelius: The Swan of Tuonela

Sibelius: Violin Sonatina

Stravinsky: Four Norwegian Moods

Symphonic Disco Spectacular

Vaughan Williams: A Pastoral Symphony

Vaughan Williams: Linden Lea

Vaughan Williams: Symphony No.4

Vaughan Williams: Tallis Fantasia

Walton: Richard III – Prelude

Waxman: Carmen Fantasy

27 Saturday Feb 2016

Posted in Uncategorized

The Birmingham Post isn’t always able to post online everything that I’ve written for its print edition, so – after a suitable time lag (you should really go out and buy the paper!) – I’ll be posting my recent reviews here. As per the print edition, they’re all fairly concise – just 250 words. This is of a performance at Symphony Hall on Saturday 13 February.

When a pianist directs a concerto from the keyboard, it’s supposed to be a liberation. Soloist and orchestra commune together without any distraction from that tiresome character with the baton: the result is like large-scale chamber music. Well that’s the theory, anyway. It stands or falls on the soloist’s basic ability to keep the whole thing in time.

There was never any likelihood of that being an issue in this final instalment of Rudolf Buchbinder’s Beethoven concerto cycle with the CBSO. The CBSO players are too skilled, too alert and too consummately professional to let anything fall down on the job. And with leader Zoë Beyers gesturing heroically from the front desk, the orchestral playing was crisper, smarter and more characterful than you’d think possible from Buchbinder’s vague, infrequent hand gestures.

If only he’d stuck to the piano! Buchbinder’s a hugely experienced artist, and the warmth of his reception shows that he has a natural connection with the Symphony Hall audience. But with his role split two ways, he never sounded wholly comfortable. Moments – a chain of translucent, feather-weight chords in the Largo of the First Concerto, the rapturous way he spun the melodic line over the Adagio of the Emperor concerto – showed what Buchbinder might have given us under different circumstances. Elsewhere cadenzas sounded fumbled, his fortissimos clangourous and harsh.

Of the two works in this short concert, it was the Emperor that came off best, taken at a cracking pace with a martial swagger that made the most of Buchbinder’s sometimes breathless approach. The First Concerto, by contrast, was baggy, and while the CBSO woodwinds delivered some lovely solos (Buchbinder gave clarinettist Oliver Janes a well-deserved bow), this was Beethoven as prose rather than poetry. You couldn’t help feeling that both soloist and orchestra were sketching only the bare outlines of the performances they would have given if a conductor had been present.