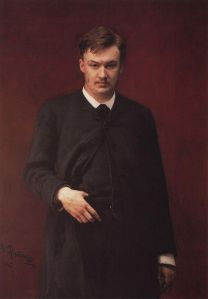

Yes, Alexander “Sasha” Konstantinovich Glazunov, “Russian Mendelssohn”, child prodigy, favourite pupil of Rimsky-Korsakov, cellist, master symphonist (and rather fine composer for string quartet too), admired teacher of Shostakovich, rather less-admired teacher of Stravinsky and Prokofiev (and unsurprisingly – once you know Glazunov’s music, all sorts of Stravinsky and Prokofiev musical mannerisms seem noticeably less original), inventor of the saxophone quartet (well, pretty much) and legendary vodka drinker, is 150 years old today. Noticed all the anniversary programming, the symphony cycles, the themed night at the Proms? No, me neither.

I’m not going to give you the full range of my thoughts and theories about this special favourite composer of mine right now. (If anyone would like to commission a biography, though…) Instead, to mark the occasion, here’s a programme note I wrote for his wonderful String Quintet Op.39 a few years back. With no word limit, I may perhaps have let my enthusiasm to make Glazunov’s case run away with me: ah well, le coeur a ses raisons…

Opportunities to write about Glazunov don’t come round as often as I’d like: just the Violin Concerto and Saxophone Quartet in recent years. So, if anyone needs anything – anything at all – writing about this incredibly likeable and under-valued composer, you know where to find me! (And I’ll do it for a discount).

“He was a charming boy, with beautiful eyes, who played the piano very clumsily. Elementary theory and solfeggio proved unnecessary for him, as he had a superior ear…after a few lessons in harmony I took him directly into counterpoint, to which he applied himself zealously. Thus his work at counterpoint and composition went on simultaneously…His musical development progressed not by the day, but literally by the hour.”

That’s how Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov recalled the extraordinary musical phenomenon of the teenage Alexander Glazunov. Balakirev, leader of the so-called “Mighty Handful” of Russian nationalist composers, had already dubbed this bright and engaging son of a St Petersburg publisher “our little Glinka”. By the time Rimsky-Korsakov took his musical education in hand, in 1880, this had turned to talk of a “Russian Mozart”. In March 1882, when Glazunov’s First Symphony was premiered under Balakirev, it caused a sensation. “The audience was astonished” writes Rimsky-Korsakov “when, in response to calls for the composer, a 17 year old boy took the stage in his school uniform.” “This is our Samson!” exclaimed the critic Vladimir Stasov.

Received opinion today has it that Glazunov’s career went pretty much downhill from there. Of course, that’s untrue. Glazunov’s style was yet to peak, and when it did, it combined a sweet and expansive melodic gift with a sparkling sense of orchestral colour. His technical skill was breathtaking. The work we know today as Borodin’s Prince Igor overture was actually written down by Glazunov from memory after Borodin’s death – Glazunov having heard it played through by the composer on the piano. His own eight symphonies have been described as “Rachmaninov on a sunny day”, though the 6th and 8th are works of genuine dramatic power, and the 4th and 5th are gloriously colourful – and could have been written by no-one else. But he was at his most inspired in genres that played to his twin strengths of orchestral colour and long-breathed melody. His Violin Concerto (1904) is still a favourite, and his masterpiece – the one-act ballet The Seasons (1899) – is arguably the greatest ballet score by any composer between The Nutcracker and Petrushka.

And that’s part of the problem – music that charmed and delighted “Silver Age” Imperial Russia looked old-fashioned after 1917. Glazunov was by then Director of the St Petersburg Conservatoire, and although he combined impeccably liberal politics with a courageous and dogged determination to protect his students’ creative freedom, he was an easy target for fashionable radicals, even amongst his own pupils.

The young Prokofiev publicly ridiculed Glazunov (though it’s easy to hear Glazunov’s influence on his own orchestration), and Igor Stravinsky consistently belittled his teacher’s music. It’s not hard to work out why – once you’ve heard The Seasons, Petrushka and Le Sacre de Printemps sound a lot less original. Tellingly, the least socially-privileged of Glazunov’s great pupils, Dmitri Shostakovich, told a rather different story: “a figure of epochal public resonance, a historic figure without exaggeration…blessed for his good deeds by every working musician in the country”. But in 1928 Glazunov, lonely and increasingly isolated, left Russia for France, where he died in 1936.

Glazunov’s reputation has still to receive a truly balanced reassessment – Stravinsky’s venom has blinded two generations of western commentators – but there’s a case to be made for his role as the father of modern Russian chamber music. The teenage Glazunov was an accomplished cellist, and his early patron Mitrofan Belaiev (who founded his own publishing house specially to print Glazunov’s music) hosted regular Friday string quartet soirees. From the earliest years, chamber music was central to Glazunov’s creative life.

Other Russian composers had written quartets and Borodin’s quartet style – lucid, lyrical, and sprinkled with colourful instrumental devices like double stopping, pizzicato and harmonics – was an unmistakable influence on the young Glazunov. But Glazunov was the first Russian composer to write an extended cycle of string quartets, seven in all between 1880 (his Op.1) and 1930, as well as numerous superbly crafted miniatures for string quartet, a brass quartet and a pioneering saxophone quartet (1932). And he wrote as an “insider”, like Haydn, Mendelssohn, and Frank Bridge, with a performer’s instinct for effective and playable string writing. His chamber music may be neglected – but, once you’ve heard it, you can’t miss its influence throughout the quartets of Miaskovsky, Prokofiev (whether he liked it or not) and, supremely, Shostakovich.

His only String Quintet may be the most perfect chamber work he wrote. Dating from 1892, and written for the influential Imperial Russian Music Society in St Petersburg, it’s scored for the same combination as Schubert’s String Quintet – two cellos rather than Mozart’s two violas. To a composer as given to lushness and lyricism as Glazunov, that seems to have been like an open invitation.

Every aspect of Glazunov’s mature style finds expression in this sunlit work. It’s all there: in the first movement, his gift for rhapsodic melody (the opening viola theme) and expansive optimism (the soaring second group). His “musical box” ballet style, in the deliciously scored pizzicato scherzo (possibly a homage to Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony – or any number of Russian nationalist balalaika-imitations from Glinka onwards). His poignant and unfailingly poetic Slav melancholy – turning to real emotion as the Andante sostenuto builds towards its impassioned climax. And his consummate ability to entertain and delight – in a finale that pays its respects to his Russian nationalist roots (that folk-dance first theme), his Conservatoire training (plenty of bustling mock-fugal stage-business) and the great Russian tradition of the big romantic tune, before speeding to an exuberant finish. The Belaiev circle weren’t really the types to dash vodka glasses in the fireplace – but Glazunov’s closing bars certainly suggest a few shot-glasses being cheerfully clinked in friendship.

Bravo! You are an intelligent critic! Yes, that whole idea of “it all went down hill from there” I think is very trite and simplistic way to describe Glazunov which I’ve definitely seen critics do. He’s a much more complex composer than that, who underwent a lot of stylistic changes and yet kept to his core values. A couple years ago I read a horrid review of the Quintet, so I’m glad you’re here to balance out such strangely hostile sentiments he gets these days. Cheers to you on his birthday! Also Prokofiev may have hated his music, but he and Glazunov certainly had respectful, even friendly relations, unlike Stravinsky.

LikeLike

I couldn’t agree more. I consider it nothing short of scandalous that not a single piece by this great composer is included in the Proms this year. When the Proms have finished, I’ll have my own “Proms”, playing nothing but Glazunov for a week.

How can so fine a melodist be so completely ignored. I’m sure that if some of the symphonies were played at concerts, people would realise what they are missing and his music would become popular again.

At least it would be a lot better that a lot of the new commissions that we seem to be plagued with every year at the Proms.

LikeLike

As I promised myself, I began my Glazunov “Proms” today with The Seasons ballet music, a short song “From Hafiz”, his superb violin concerto played by Nathan Milstein – why this is not in the repertoire along with the Seasons is beyond me – and finished off today with his symphonic poem Stenka Razin. I can’t wait to discover what I will play for the rest of the week!!!

LikeLike